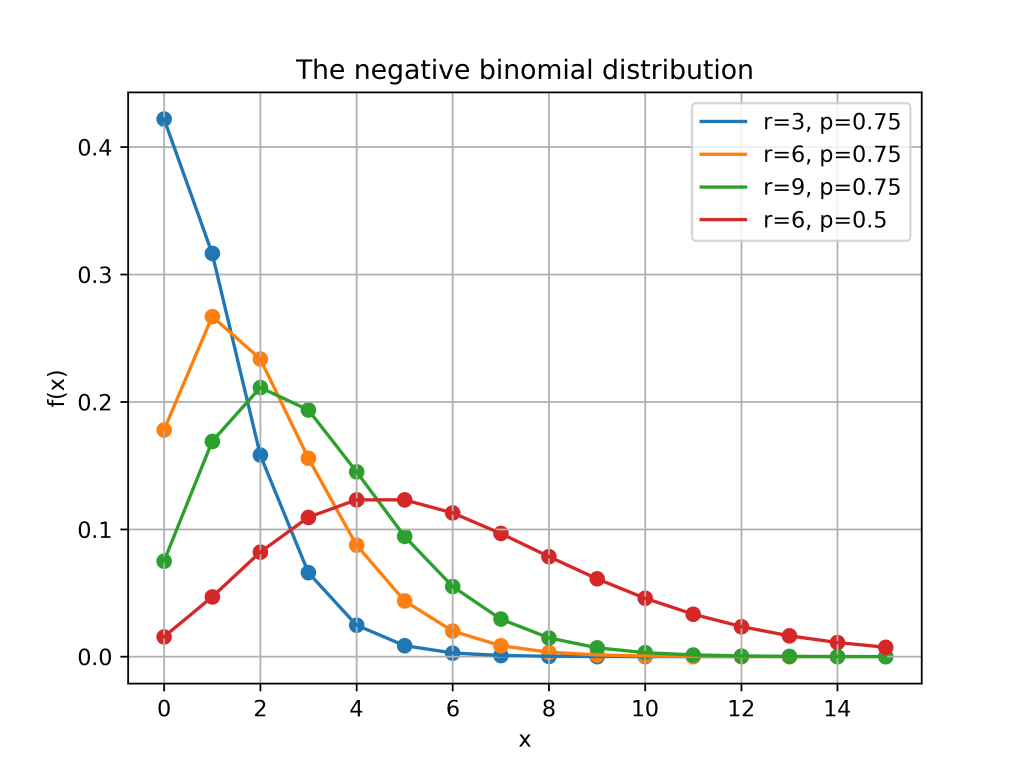

This post is an introduction to the negative binomial distribution and a discussion of different ways of approximating the negative binomial distribution.

The negative binomial distribution describes the number of times a coin lands on tails before a certain number of heads are recorded. The distribution depends on two parameters and

. The parameter

is the probability that the coin lands on heads and

is the number of heads. If

has the negative binomial distribution, then

means in the first

tosses of the coin, there were

heads and that toss number

was a head. This means that the probability that

is given by

Here is a plot of the function for different values of

and

.

Poisson approximations

When the parameter is large and

is close to one, the negative binomial distribution can be approximated by a Poisson distribution. More formally, suppose that

for some positive real number

. If

is large then, the negative binomial random variable with parameters

and

, converges to a Poisson random variable with parameter

. This is illustrated in the picture below where three negative binomial distributions with

approach the Poisson distribution with

.

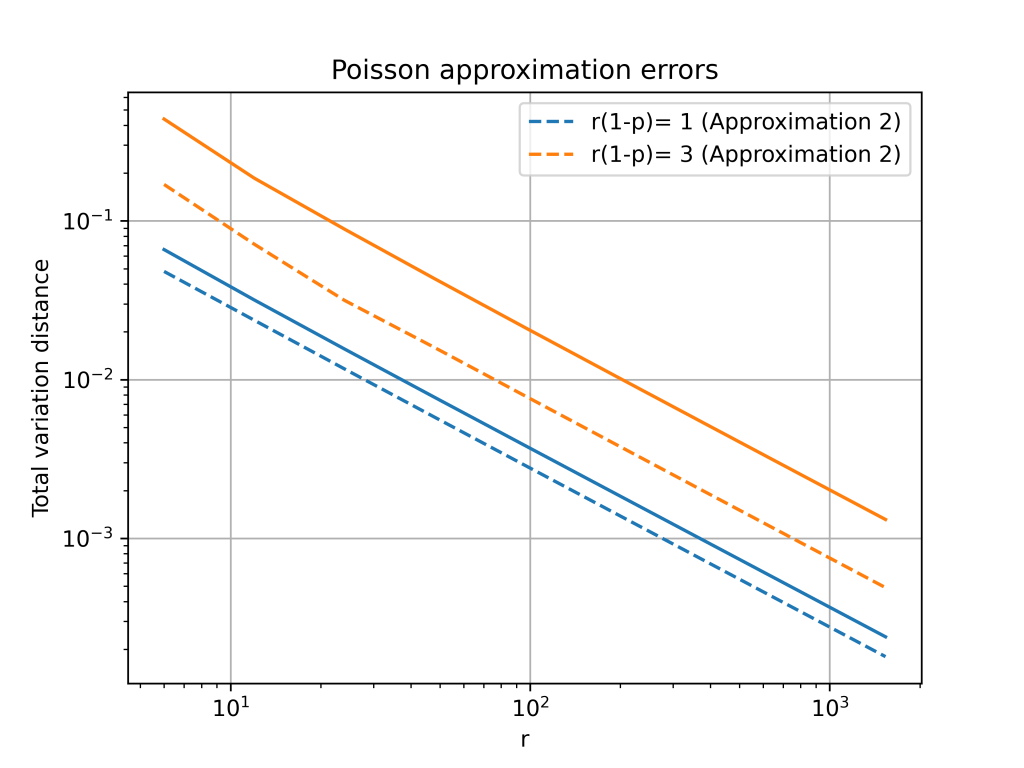

Total variation distance is a common way to measure the distance between two discrete probability distributions. The log-log plot below shows that the error from the Poisson approximation is on the order of and that the error is bigger if the limiting value of

is larger.

It turns out that is is possible to get a more accurate approximation by using a different Poisson distribution. In the first approximation, we used a Poisson random variable with mean . However, the mean of the negative binomial distribution is

. This suggests that we can get a better approximation by setting

.

The change from to

is a small because

. However, this small change gives a much better approximation, especially for larger values of

. The below plot shows that both approximations have errors on the order of

, but the constant for the second approximation is much better.

Second order accurate approximation

It is possible to further improve the Poisson approximation by using a Gram–Charlier expansion. A Gram–Charlier approximation for the Poisson distribution is given in this paper.1 The approximation is

where as in the second Poisson approximation and

is the Poisson pmf evaluated at

.

The Gram–Charlier expansion is considerably more accurate than either Poisson approximation. The errors are on the order of . This higher accuracy means that the error curves for the Gram–Charlier expansion has a steeper slope.

- The approximation is given in equation (4) of the paper and is stated in terms of the CDF instead of the PMF. The equation also contains a small typo, it should say

instead of

. ↩︎