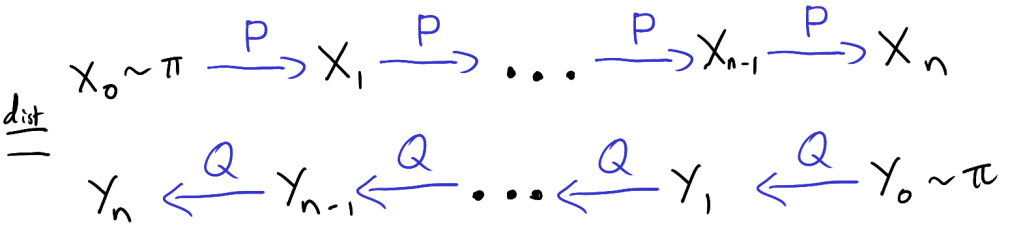

Suppose we have two samples and

and we want to test if they are from the same distribution. Many popular tests can be reinterpreted as correlation tests by pooling the two samples and introducing a dummy variable that encodes which sample each data point comes from. In this post we will see how this plays out in a simple t-test.

The equal variance t-test

In the equal variance t-test, we assume that and

, where

is unknown. Our hypothesis that

and

are from the same distribution becomes the hypothesis

. The test statistic is

,

where and

are the two sample means. The variable

is the pooled estimate of the standard deviation and is given by

.

Under the null hypothesis, follows the T-distribution with

degrees of freedom. We thus reject the null

when

exceeds the

quantile of the T-distribution.

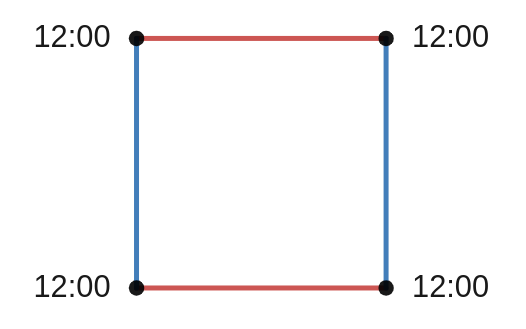

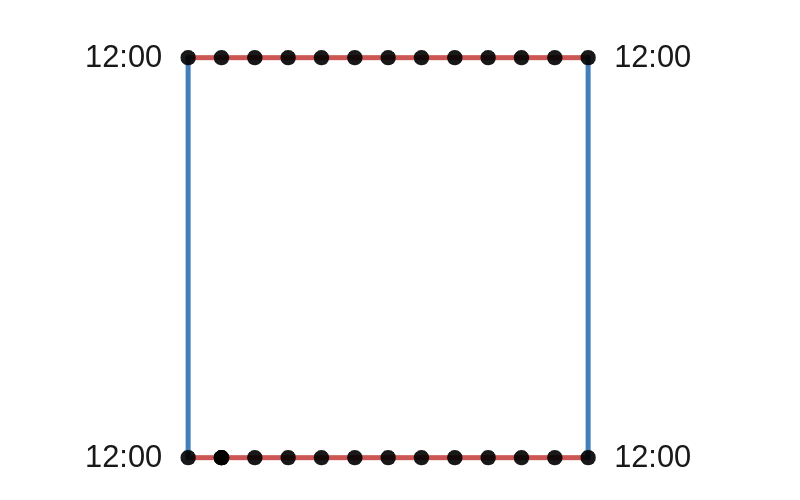

Pooling the data

We can turn this two sample test into a correlation test by pooling the data and using a linear model. Let be the pooled data and for

, define

by

The assumptions that and

can be rewritten as

where . That is, we have expressed our modelling assumptions as a linear model. When working with this linear model, the hypothesis

is equivalent to

. To test

we can use the standard t-test for a coefficient in linear model. The test statistic in this case is

where is the ordinary least squares estimate of

,

is the design matrix and

is an estimate of

given by

where is the fitted value of

.

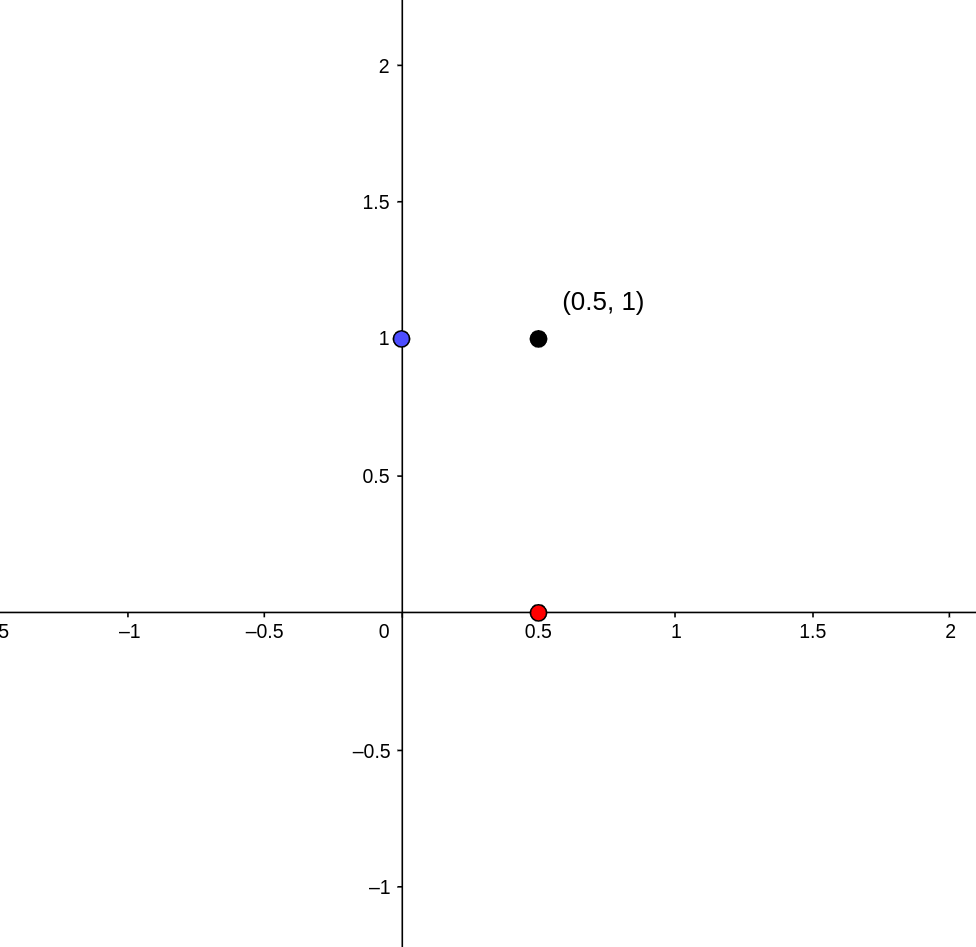

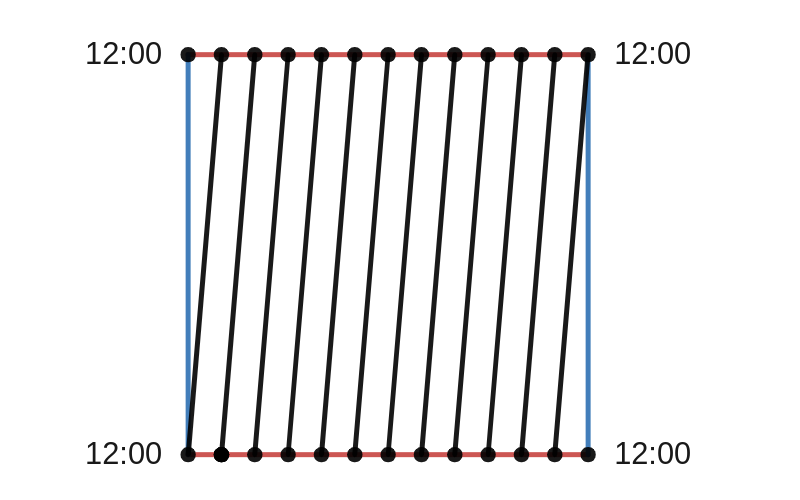

It turns out that is exactly equal to

. We can see this by writing out the design matrix and calculating everything above. The design matrix has rows

and is thus equal to

This implies that

And therefore,

Thus, . So,

which is starting to like from the two-sample test. Now

And so

Thus, and

This means to show that , we only need to show that

. To do this, note that the fitted values

are equal to

Thus,

Which is exactly . Therefore,

and the two sample t-test is equivalent to a correlation test.

The Friedman-Rafsky test

In the above example, we saw that the two sample t-test was a special case of the t-test for regressions. This is neat but both tests make very strong assumptions about the data. However, the same thing happens in a more interesting non-parametric setting.

In their 1979 paper, Jerome Friedman and Lawrence Rafsky introduced a two sample tests that makes no assumptions about the distribution of the data. The two samples do not even have to real-valued and can instead be from any metric space. It turns out that their test is a special case of another procedure they devised for testing for association (Friedman & Rafsky, 1983). As with the t-tests above, this connection comes from pooling the two samples and introducing a dummy variable.

I plan to write a follow up post explaining these procedures but you can also read about it in Chapter 6 of Group Representations in Probability and Statistics by Persi Diaconis.

References

Persi Diaconis “Group representations in probability and statistics,” pp 104-106, Hayward, CA: Institute of Mathematical Statistics, (1988)

Jerome H. Friedman, Lawrence C. Rafsky “Multivariate Generalizations of the Wald-Wolfowitz and Smirnov Two-Sample Tests,” The Annals of Statistics, Ann. Statist. 7(4), 697-717, (July, 1979)

Jerome H. Friedman, Lawrence C. Rafsky “Graph-Theoretic Measures of Multivariate Association and Prediction,” The Annals of Statistics, Ann. Statist. 11(2), 377-391, (June, 1983).