It is winter 2022 and my PhD cohort has moved on the second quarter of our first year statistics courses. This means we’ll be learning about generalised linear models in our applied course, asymptotic statistics in our theory course and conditional expectations and martingales in our probability course.

In the first week of our probability course we’ve been busy defining and proving the existence of the conditional expectation. Our approach has been similar to how we constructed the Lebesgue integral in the previous course. Last quarter, we first defined the Lebesgue integral for simple functions, then we used a limiting argument to define the Lebesgue integral for non-negative functions and then finally we defined the Lebesgue integral for arbitrary functions by considering their positive and negative parts.

Our approach to the conditional expectation has been similar but the journey has been different. We again started with simple random variables, then progressed to non-negative random variables and then proved the existence of the conditional expectation of any arbitrary integrable random variable. Unlike the Lebesgue integral, the hardest step was proving the existence of the conditional expectation of a simple random variable. Progressing from simple random variables to arbitrary random variables was a straight forward application of the monotone convergence theorem and linearity of expectation. But to prove the existence of the conditional expectation of a simple random variable we needed to work with projections in the Hilbert space .

Unlike the Lebesgue integral, defining the conditional expectation of a simple random variable is not straight forward. One reason for this is that the conditional expectation of a random variable need not be a simple random variable. This comment was made off hand by our Professor and sparked my curiosity. The following example is what I came up with. Below I first go over some definitions and then we dive into the example.

A simple random variable with a conditional expectation that is not simple

Let be a probability space and let

be a sub-

-algebra. The conditional expectation of an integrable random variable

is a random variable

that satisfies the following two conditions:

- The random variable

is

-measurable.

- For all

,

, where

is the indicator function of

.

The conditional expectation of an integrable random variable is unique and always exists. One can think of as the expected value of

given the information in

.

A simple random variable is a random variable that take only finitely many values. Simple random variables are always integrable and so

always exists but we will see that

need not be simple.

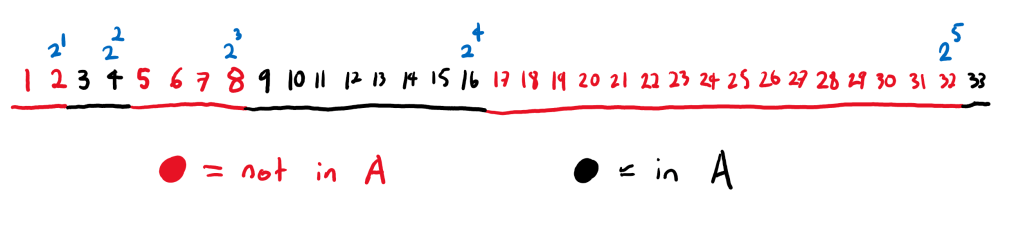

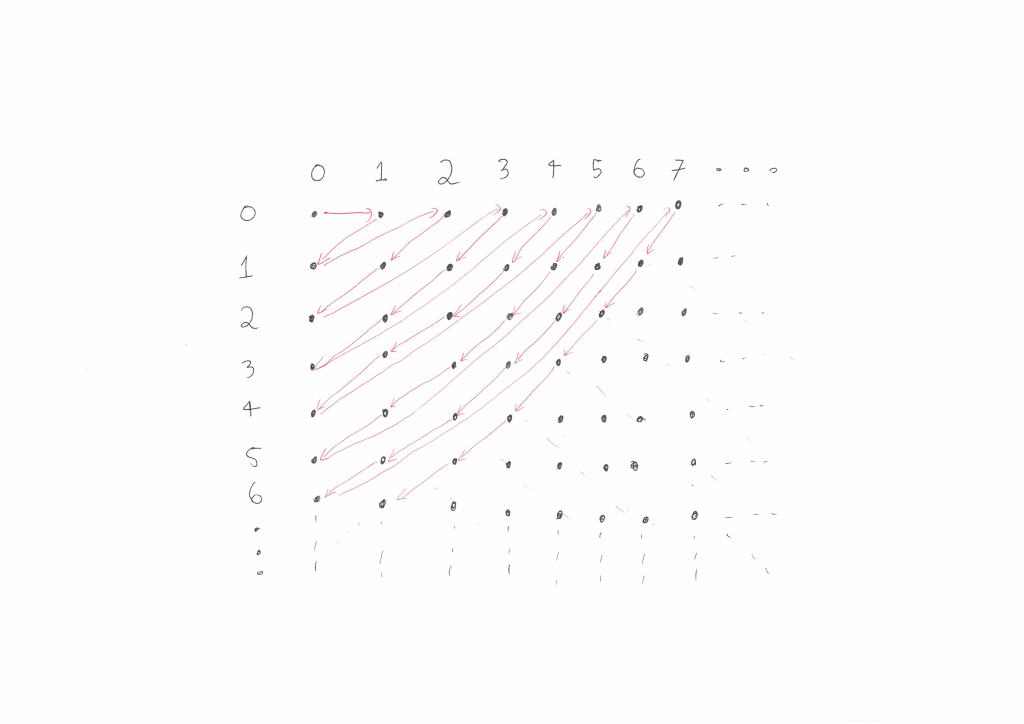

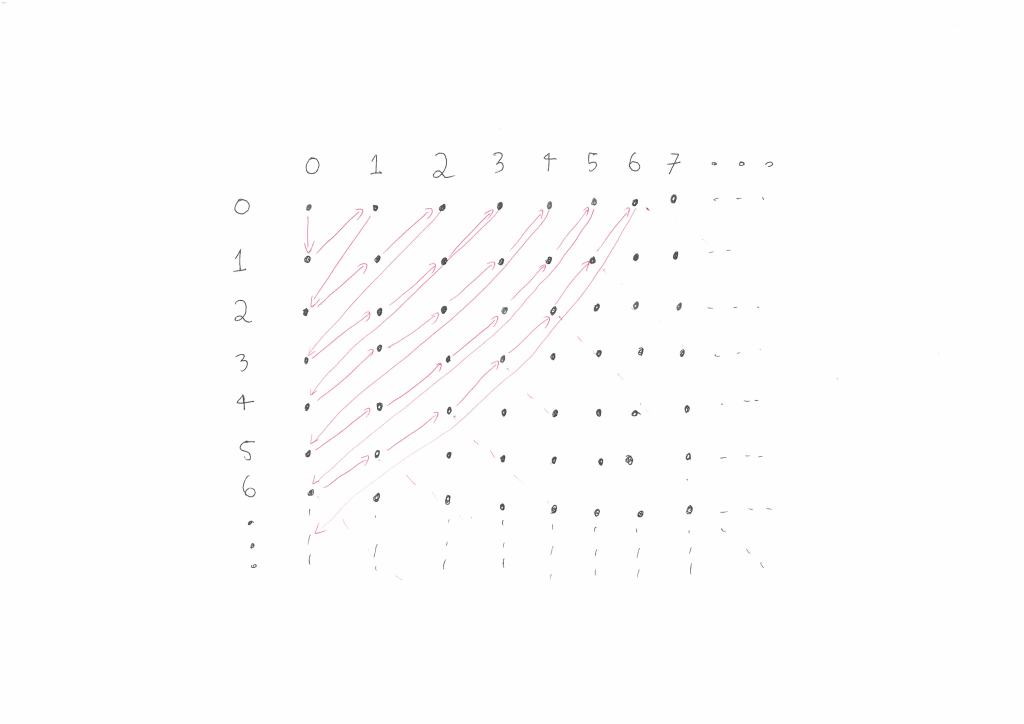

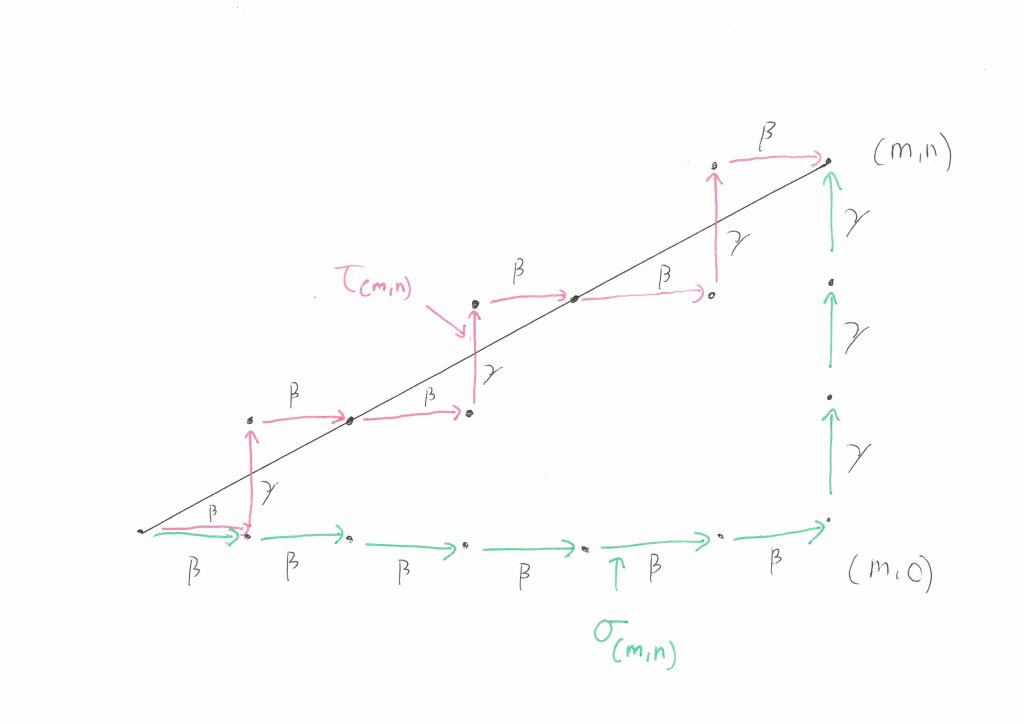

Consider a random vector uniformly distributed on the square

. Let

be the unit disc

. The random variable

is a simple random variable since

equals

if

and

equals

otherwise. Let

the

-algebra generated by

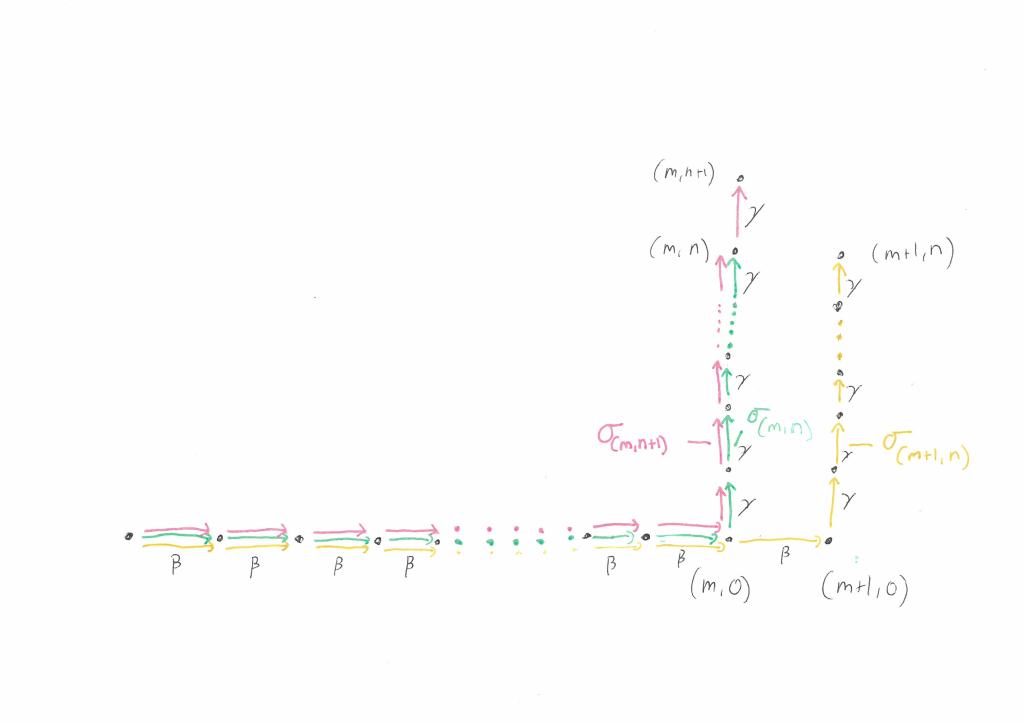

. It turns out that

.

Thus is not a simple random variable. Let

. Since

is a continuous function of

, the random variable is

-measurable. Thus

satisfies condition 1. Furthermore if

, then

for some measurable set

. Thus

equals

if and only if

and

. Since

is uniformly distributed we thus have

.

The random variable is uniformly distributed on

and thus has density

. Therefore,

.

Thus and therefore

equals

. Intuitively we can see this because given

, we know that

is

when

and that

is

otherwise. Since

is uniformly distributed on

the probability that

is in

is

. Thus given

, the expected value of

is

.

An extension

The previous example suggests an extension that shows just how “complicated” the conditional expectation of a simple random variable can be. I’ll state the extension as an exercise:

Let be any continuous function with

. With

and

as above show that there exists a measurable set

such that

.